Whisker-based Tactile Sensing and Shape Classification

active vibrissal sensing to classify concave and convex objects using ANN and invtestigation in the transformation from the whisker base frame to the head frame using RL

Overview

The objective of this project aims to replicate a rat’s active vibrissal sensing to classify concave and convex objects using artificial neural networks in simulations. Moreover, we investigated how individual whiskers affect neurons in the neural networks of the deep-q learning algorithm, which enabled the rat in simulation to find an optimal whisking orientation that maximizes the symmetry of contacting whiskers.

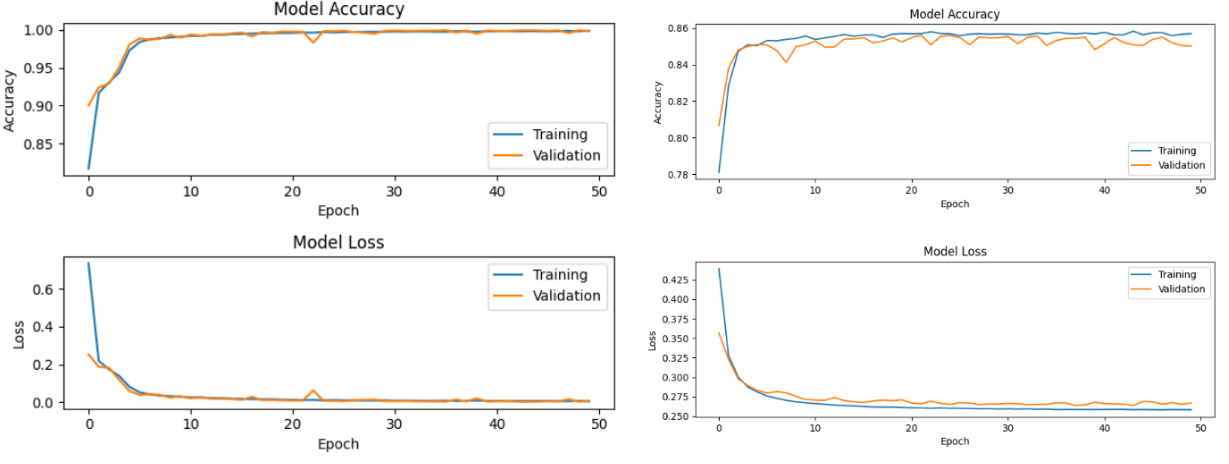

- The logistic regression model of 4 whiskers was able to classify concave and convex shapes with contact numbers with 0.81 accuracy.

- The neural network model of 4 whiskers was able to classify concave and convex shapes with peak moment with 0.92 accuracy.

- Inaccessibility to modify whisking amplitude in WHISKiT Physics simulator limited replicating Chris Rodger’s experiments.

- The neural network model of 54 whiskers was able to classify concave and convex shapes with contact duration with 0.92 accuracy while the rat was actively rotating its yaw.

- Image classification performed better than tabular data classification due to convolutional neural network that can process temporal and spatial data sufficiently

- Image classifier training was more time consuming than tabular data classifier DQN algorithm was implemented to investigate how individual whiskers affect the neural network which outputs a rat’s action to maximize symmetrical whiskers contact

Code: [GitHub]

Introduction

Inspired by the ability of animals to maneuver effectively in their environment, biomimetic robotics has led to the diverse shapes and sizes of robot design. Biomimetic robot designs attempt to translate biological principles into engineered systems, replacing more classical engineering solutions to achieve a function observed in the natural system 1.

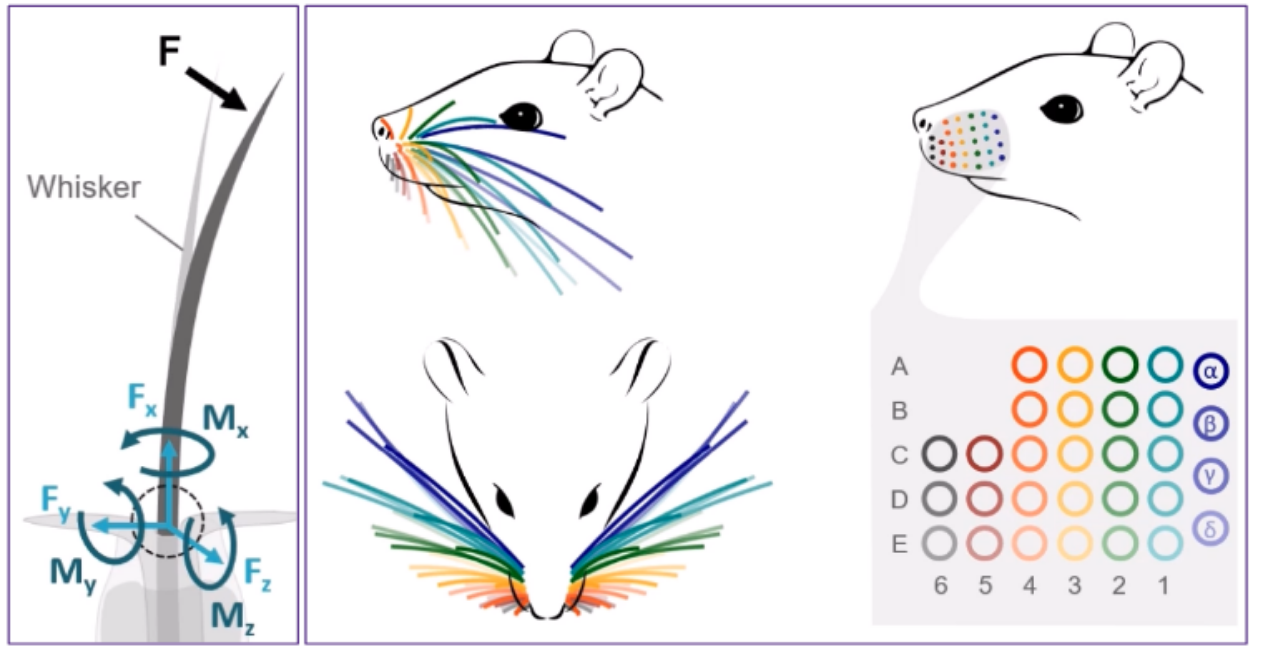

In this project, we are particularly interested in a rat’s ability to navigate intricate underground tunnels systems to the surface for scavenging in complete darkness. The rat’s exploratory behavior is dominated by intense “whisking,” rhythmic sweeps of the vibrissae (whiskers) that provide a continuous flow of tactile information to the rat’s brain. As they navigate, their whiskers make unexpected contact with an object, and the rat then explores the object to extract the details of its shape. The use of whisker inputs to detect, localize and extract the spatial properties of objects. These unique features allow rats to operate in complete darkness 2.

Studying real rats as a model is time-consuming and complex. Primarily, researchers have been unable to quantify the mechanosensory input at the base of each whisker. However, Nadina Zweifel has implemented WHISKiT Physics Simulator, and it allows us to investigate three-dimensional dynamic information of individual whisker.

When a whisker makes contact with a 3D polygon mesh object in the simulation, the simulator calculates three-dimensional forces and moments at the whisker’s base using the Bullet Physics library. Whiskers on a rat’s face exist in the form of matrices with their inherent names and functionality. This project will primarily investigate the transformation from the whisker base frame to the head frame using neural networcoordinateks to replicate a rat’s behavior during active whisking.

Objectives

While the contents of this project are wildly divergent, we have main objectives, which are the following two.

Concave and Convex Shape Classification Model

- We have a lot of information coming from multiple whiskers. By varying the training input and neural network structure, we can explore the minimal requirement to perform successful concave-convex classification tasks.

- Implementation of real-time classification verifies the quality of the classification model. We can change the diameters of objects or the orientation of the rat to observe how those changes affect the classification result.

Reinforcement Learning and the Coordinate Transformation

- A rat tends to bring its snout to the object as close as possible while ensuring whiskers contact the object symmetrically. We can use deep-q learning algorithms to replicate this behavior in the simulation.

- After sufficient training, we can evaluate the weights of each whisker to neurons in the input layer. We can investigate how an individual whisker affects the neural network to output the rat’s action during active sensing in the simulation (coordinate transformation from whisker frame to the head frame).

Results

Comparison to Rodger’s Experiment: Classification with Contact Number

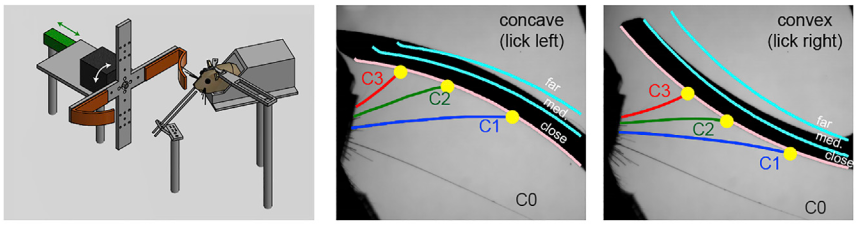

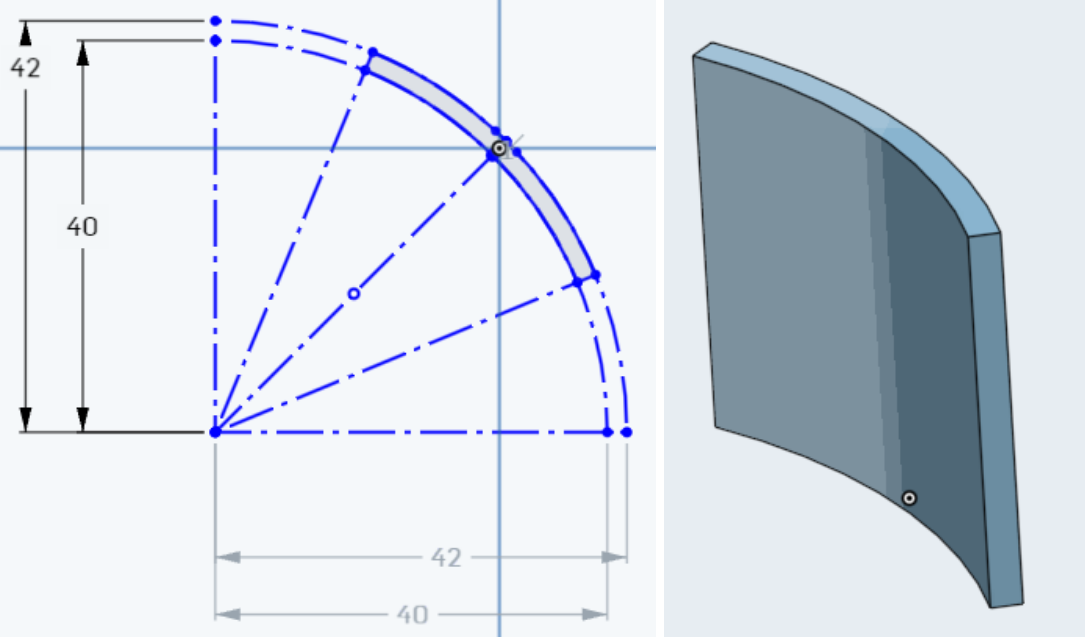

In his research, Chris Rodgers suggests that mice compared the number of contacts across whiskers to discriminate concave and convex shapes [4]. We replicated his experiment in simulations. Since Rodgers did not provide exact parameters for the experiment apparatus, such as radius of objects and distance between the mice and objects, we estimated those parameters from figures and videos. We created 3D modeling of a concave object with a 40 mm inner radius and a 42 outer radius with 25 mm height using Onshape.

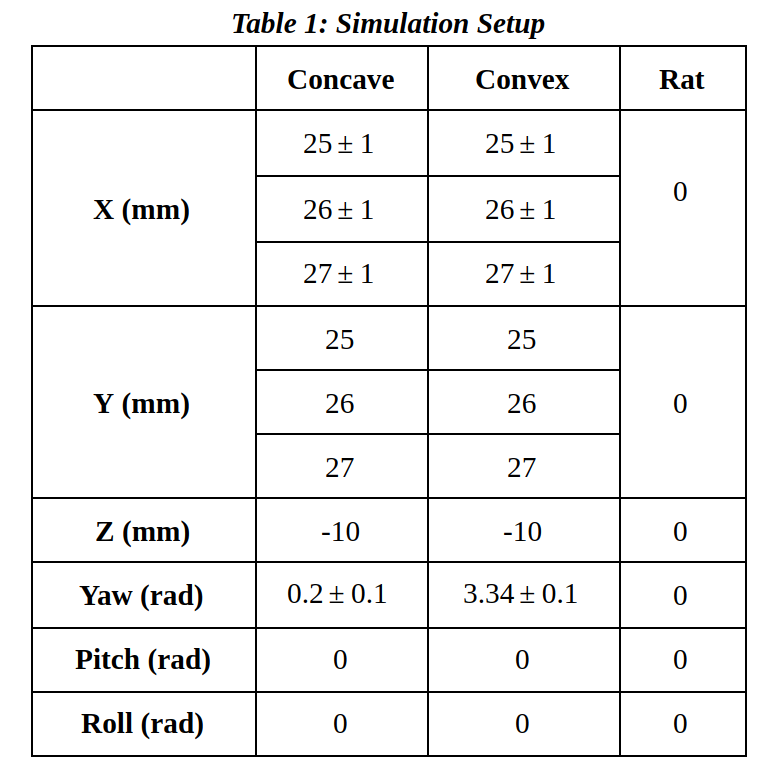

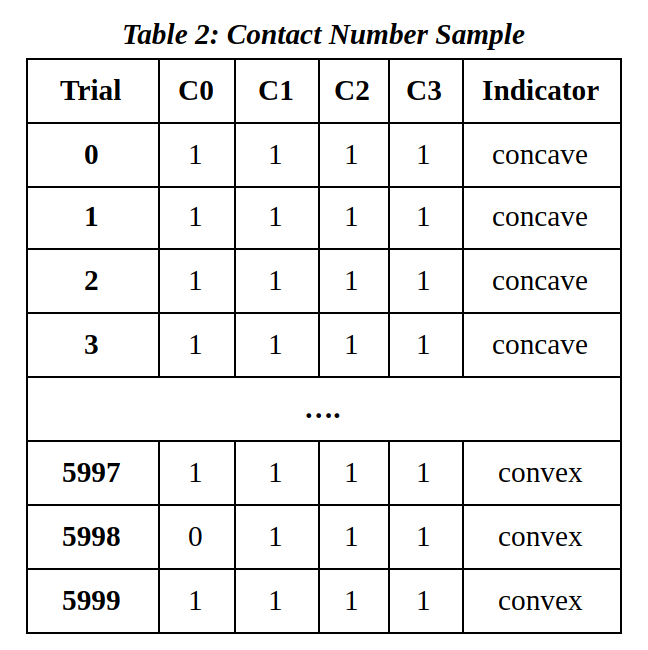

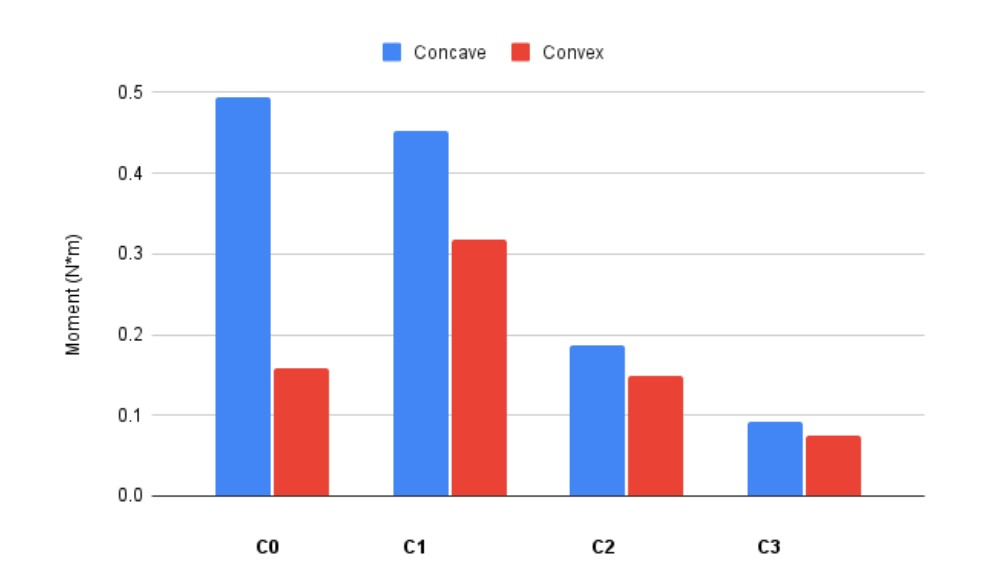

The simulation involved 3 different positions for both concave and convex objects adjusted with small variations of noise. For each orientation of the object, one cycle of whisking with C0, C1, C2, and C3 right whiskers was simulated 1,000 times to obtain a total of 6,000 samples of contact data. Table 2 below shows some samples of binary contact data. If a whisker made contact with an object anytime during the trial (one cycle of whisking), it received 1 to indicate contact. Figure 6 below shows the general trend of the data. Concave objects experienced a longer duration of contact compared to the convex objects overall, and C0 showed a significant difference between the concave and convex objects.

A binary classifier was implemented using logistic regression to discriminate concave and convex objects with contact numbers, and its accuracy was 0.81. However, Rodgers mentions he did not include C0 data in his analysis since the C0 whisker rarely touched the object during his experiments. Training and testing without C0 data, my logistic regression classifier could not perform its task with an accuracy rate below 0.5.

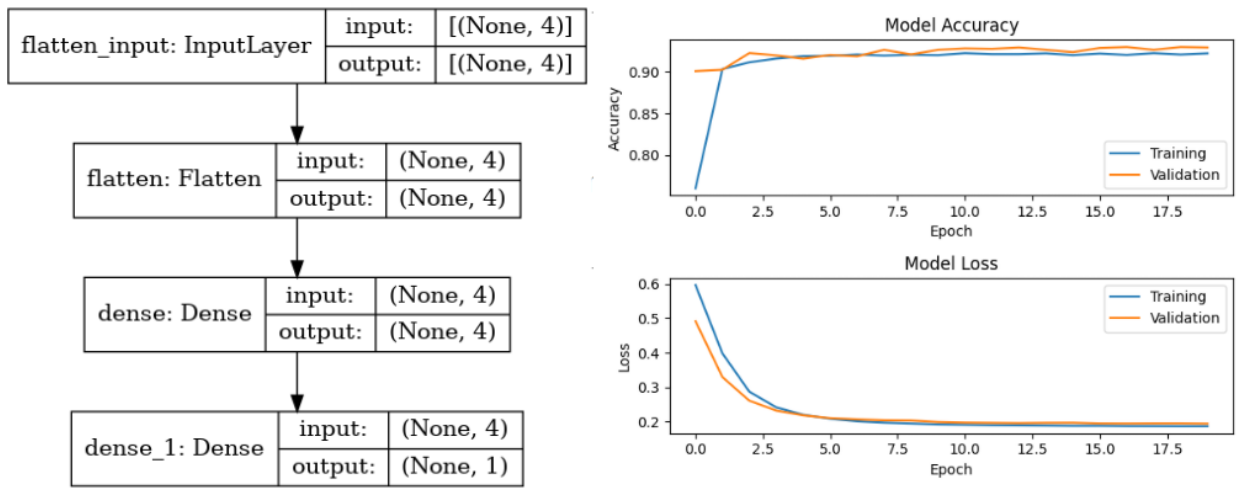

Four Whiskers Task: Classification with Moment

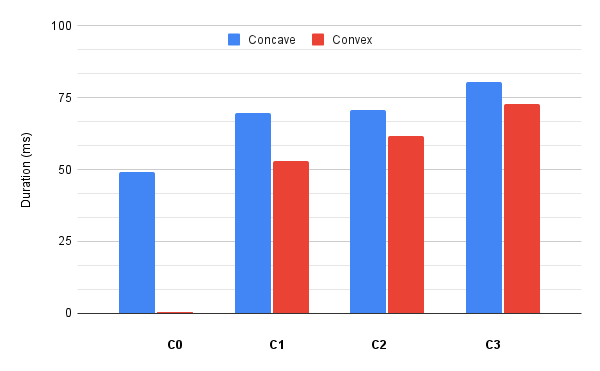

Taking advantage of other types of data we obtained from the simulation, we expanded our classifier to train moment data. We calculated the magnitude of peak protraction moment excluding Mx for each trial, trained with logistic regression, and had the result of the accuracy of 0.84. Since moment data contained a more complex data type than binary contact data, we built a neural network-based classifier with Tensorflow and Keras. The classification accuracy improved to 0.92 using one hidden layer with four neurons.

While training input only contained simulation output with a fixed rat head orientation, we investigated how changing the pitch (looking up and down motion) affected classification accuracy. Video 1 shows the real-time classification with a pre-trained model (refer to Figure 7 for detailed information for the model). Gradually increasing the pitch, the classification failed around 26 degrees incrementation. The classification accuracy dropped significantly when the C0 whisker did not make contact. Since the model only takes inputs from four whiskers, each whisker takes a large proportion of classification accuracy. Hence, we proceeded with a different simulation setup to utilize all whiskers.

All Whiskers Simulation

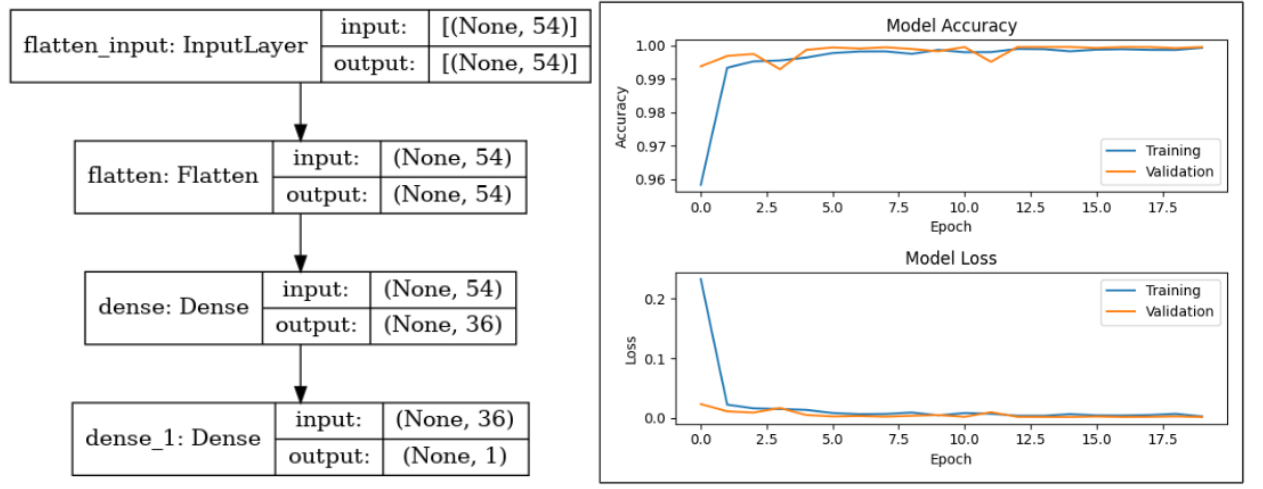

Utilizing more whiskers can increase the real-time classification performance while the rat is actively rotating and moving its head. Therefore, whisking over concave and convex objects was simulated using all 54 whiskers and 22 concave and convex objects with different radius. The inner radius of both concave and convex objects varied 20 mm to 40 mm by 2 mm increment. An object was placed at [X: 0 mm, Y: 30 mm, and Z: -10 mm, Yaw: 0.2 rad (concave) or 3.34 (convex), Pitch: 0 rad, Roll: 0 rad] configuration. The orientation of the rat head was varied by randomly adjusting the yaw of the rat head by +-90 degrees. Five cycles of whisking over each object were simulated 1,200 times, outputting 132,000 samples. Each sample contained data of force, moment, and contact of 54 whiskers during one cycle of whisking (125 ms in simulation time).

All Whiskers Classification: Contact Duration

One cycle of whisking takes 125 ms in the simulation time, and contact duration is determined by how long the whisker made contact with the object during one cycle of whisking. This data was used to build a classifier. It converged to 0.99 accuracies using one hidden layer with 36 neurons which is ⅔ of the input size. This model was verified with a real-time classification which allowed the rat head’s forward motion and rotation in the yaw axis. Video 2 demonstrates the real-time classification of a moving rat head with a concave object. The classification failed when not a sufficient number of whiskers were making contact with the objects. This result leads us to the next step of the project to ensure the rat’s optimal orientation while actively whisking.

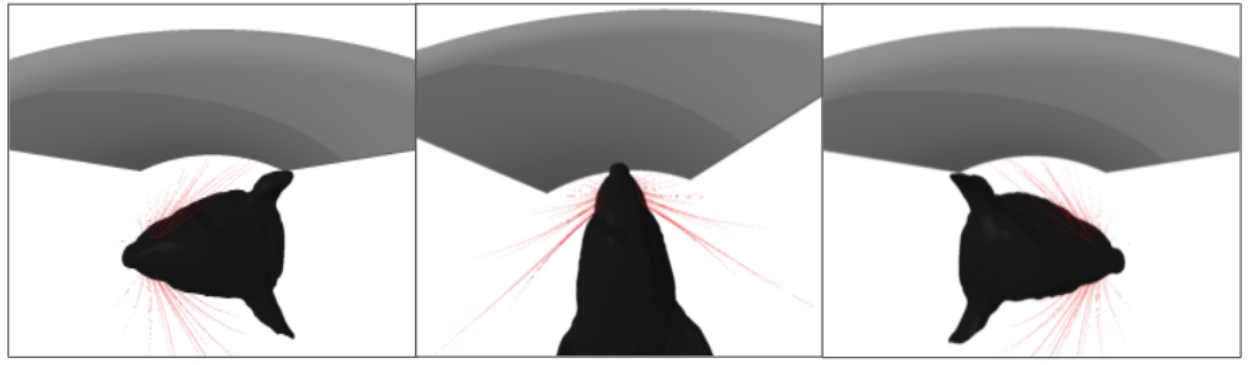

Reinforcement Learning and Coordinate Transformation

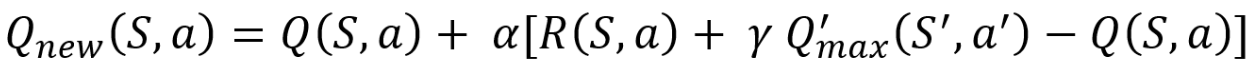

We have witnessed how the orientation of a rat’s head during active whisking affects classification performance. We implemented a model which enables symmetric contact of whiskers while maximizing the contact number using the Deep-Q learning algorithm.

During simulation, the q-function is updated upon every action the rat takes. The rat has five actions which are: [turn right, turn left, look up, look down, stay]. Gamma decides which rat should take its next action based on the q-function or completely random action. The rat takes random actions due to limited information in the q-function. As the training progresses, the gamma value is adjusted to encourage the rat to take action based on q-function. Alpha is a learning rate that affects how much the neural network will embrace the new value replacing the existing value. The learning rate in the training depends on the protraction status of the whiskers. The learning rate is proportional to the angle of whiskers to weight information received during peak protraction.

The symmetrical contact of whiskers and contact number decide the reward value. Contact symmetry is weighted more heavily than a contact number to replicate a real rat’s behavior. When the sum of rewards of one cycle of whisking does not reach the given threshold, the rat head orientation is set to the default position and receives a negative reward.

Discussion

Whisking Amplitude Adjustment is Necessary To Replicate a Real Rat

Rodgers states that he excluded the C0 whisker from his analysis since “it rarely made contact with the object”. However, my simulation result suggests that the C0 whisker contains significant information to distinguish between concave and convex shapes as seen in Figure 6. Neither contact number nor peak moment model performed classification task without training the C0 data. While a real rat can adjust the whisking amplitude, the simulator follows a given time-specified whisking trajectory. Therefore, we concluded that it was not feasible to fully replicate Rodger’s experiment due to the limits of the WHISKiT Physics Simulator.

Temporal dependent Input Data Allows Successful Classification

The rat successfully classified concave and convex objects with 54 whiskers while actively adjusting its orientation. This model was trained with one hidden layer with 36 neurons. The number of neurons was decided by factoring ⅔ to the input size. Adjusting the number of neurons in the hidden layer changed convergence time, but it did not significantly affect the classification accuracy.

Besides contact duration classifiers, other types of classifiers use more high-level dynamic data input such as the averages of moments, derivatives of moments, averages of forces, and derivatives of forces of each whisker. They all successfully converged to 0.99 accuracies and outperformed in real-time classification. On the other hand, the contact number and peak moment classifier lacked the capabilities to process simulation output from various yaw angles of the rat head since they underperformed with around 0.85 accuracies. We concluded that data such as contact duration involves time-dependent information, and it allows successful classification with non-fixed head orientation.

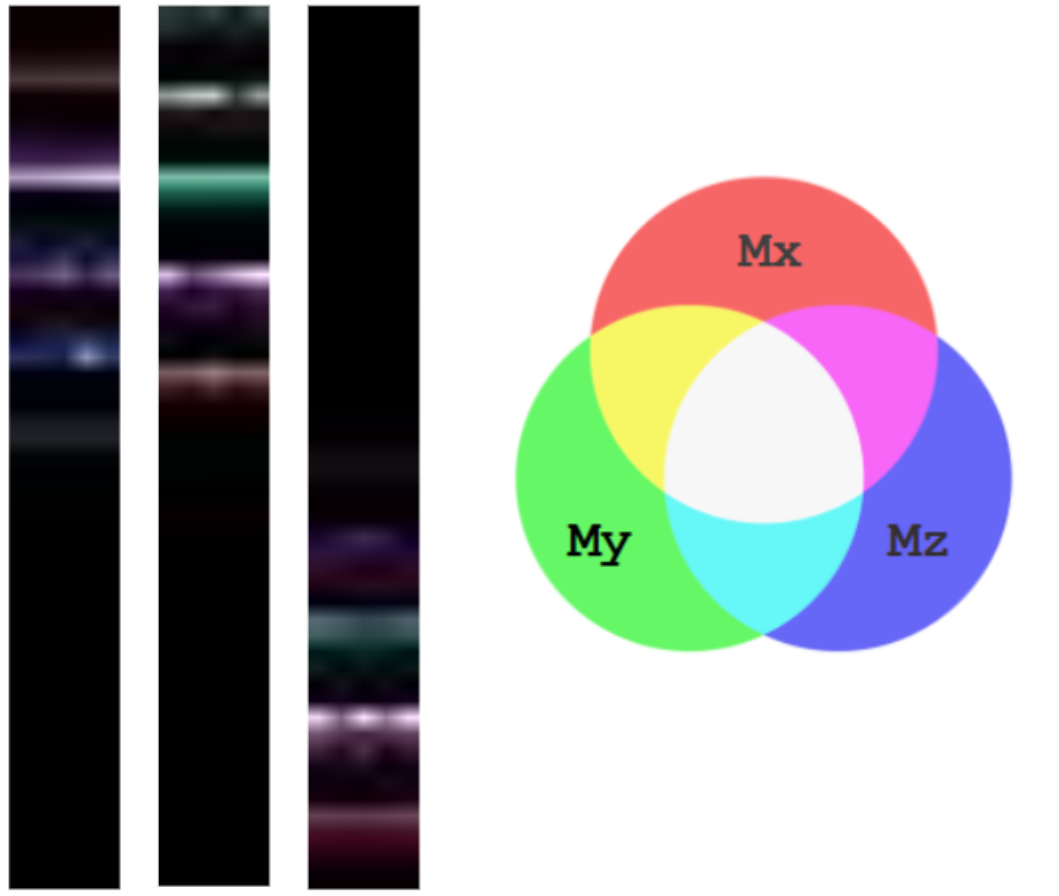

Contact Data Conversion to Gray Image

Data from whiskers have temporal and spatial dependencies. However, the WHISKiT Physics Simulator saves its results as tabular data. In his paper, Zhu states that most tabular data do not assume a spatial and temporal relationship between features. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) are inspired by visual neuroscience and possess key features that exploit the properties of natural signals, including local connections in receptive fields, parameter sharing via convolution kernel, and hierarchical feature abstraction through pooling and multiple layers. These features make CNNs suitable for analyzing data with spatial or temporal dependencies between components 4.

Hence we attempted to convert tabular data to images to train CNN based classifiers. While the image row represents each whisker, the column represents time series in simulation. Data is fed into a 2D array 0 as no-contact and 255 as contact to make a gray-scale image, and we are able to visualize when and where the whiskers made contact with objects during the simulation.

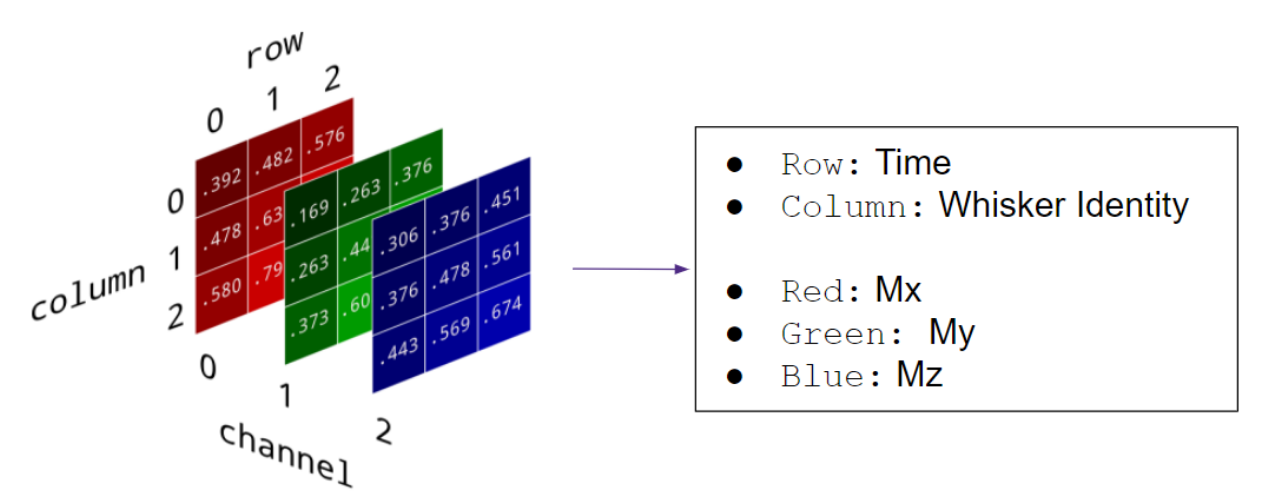

Moment Data Conversion to RGB Image

The same concept can be applied to three-dimensional force data. Inserting Mx data into a red layer, My into a green layer, and Mz into a blue layer, we can represent each moment data with whisker type and time as separate dimensions.

Since data is normalized for images, it is not feasible to produce a real-time RGB image unless color values are pre-defined as ranges. However, these RGB images allow us to interpret the data easily with an RGB combination diagram. Figure 14 shows the average three-dimensional moment during five cycles of whisking. Training image classifiers was more time-consuming than tabular data classifiers. Since concave and convex simulation was simple enough to use contact duration tabular classifiers and had 0.99 accuracy, training image classifiers were not further investigated.

Conclusion

In this project, we investigated neural networks for concave and convex shape classification. This task was achieved using tabular data training, but future works that require more complicated multi-class classification will require image classification. We will plan to modify WHISKiT Physics Simulator to compare to Rodger’s experiment. It was especially challenging to implement temporal dependencies in the DQN algorithm. Since previous actions taken by the rat affects the present reward, we had to keep track of real-time reward that captures real-time contact data and long-time reward which evaluates the whisking performance of each cycle. Moreover, it was crucial that the simulator does not have multi-threading functions. Training DQN was time-consuming due to the slow physics calculations of each whisker.

CITATION

[1] Cho KJ., Wood R. (2016) Biomimetic Robots. In: Siciliano B., Khatib O. (eds) Springer Handbook of Robotics. Springer Handbooks. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32552-1_23

[2] Hartmann MJ. A night in the life of a rat: vibrissal mechanics and tactile exploration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Apr;1225:110-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06007.x. PMID: 21534998.

[3] Zweifel, Nadina & Bush, Nick & Abraham, Ian & Murphey, Todd & Hartmann, Mitra. (2019). WHISKiT Physics: A three-dimensional mechanical model of the rat vibrissal array. 10.1101/862839.

[4] Zhu, Y., Brettin, T., Xia, F. et al. Converting tabular data into images for deep learning with convolutional neural networks. Sci Rep 11, 11325 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90923-y